Shoulder dislocations are common among the young, active, athletic population. A shoulder dislocation is defined when the humerus, or upper arm bone, is forced away from the glenoid, or shoulder bone completely. The humerus dislocates toward the front (anterior) in most patients, but it can dislocate toward the back (posterior). This injury can lead to damage of the soft tissue structures called the labrum and capsule, made of cartilage and connective tissue, that help stabilize the shoulder joint. This dislocation can also cause an injury to the rotator cuff or damage to the bone. If the damage to the labrum, the rotator cuff, or the bone is severe enough, then it can lead to long-term instability or multiple dislocations.

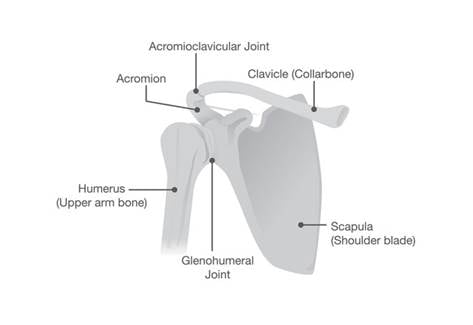

Figure 1: Normal shoulder anatomy

The bone structure of the shoulder is composed of the scapula which forms the socket (or glenoid) and the humerus which is the ball (see Figure 1). The structure is very similar to a larger golf ball sitting on a smaller golf tee. The bone anatomy is inherently unstable, but the labrum and the capsule increase the stability. The rotator cuff provides the dynamic muscle pull for stability.

Figure 2: MRI scan showing dislocation of the shoulder (Golf ball has fallen off the golf tee)

Treatment is based on proper evaluation and diagnosis of the injury. The exact treatment depends on the physical damage, the athlete’s level of activity, the future goals, and the number of times this dislocation has occurred. The diagnosis requires the physician understanding the history of the problem, a physical exam, an x-ray, and an MRI with dye injected into the joint. From this evaluation, the treatment plan can be completed.

When the shoulder dislocates the labrum can tear away from the glenoid (figure 3), the capsule and/or rotator cuff can tear, or a fracture can occur. Each of these injury patterns should be recognized and treated. The conservative (non-surgical) treatment usually begins with immobilization in a sling for 3-6 weeks. Using the sling allows for healing or “scaring in” of the structures. Following the immobilization, physical therapy or an exercise program to strengthen the rotator cuff and the shoulder blade core muscles is crucial. The healing and recovery may take up to 6 months.

Figure 3: Torn labrum from the glenoid

If the shoulder continues to have pain or continues to dislocate, then surgery may be required. The surgery is based on the type of injury and the severity of the damage. Usually, the repair can be done arthroscopically. This method uses 3-4 small incisions and a camera inserted into the joint to fix the labral tear (figure 4). We can use small anchors that are fixed into the bone and the attached sutures to put the labrum back anatomically restoring stability. Occasionally a fracture or other damage may require the need for an open surgery. Following surgery, the patient uses a sling for 4-6 weeks. Slow progression to normal activity and controlled building strength with therapy are encouraged. The long-term outcome with surgery is excellent.

Figure 4: Repair of Labrum

Shoulder dislocations are common injuries seen in the young active population. Proper evaluation and treatment can lead to excellent outcomes and return to normal function.